Prof. Ricardo Britto

Doctor in Business Administration at USP

Dean of IBS Americas

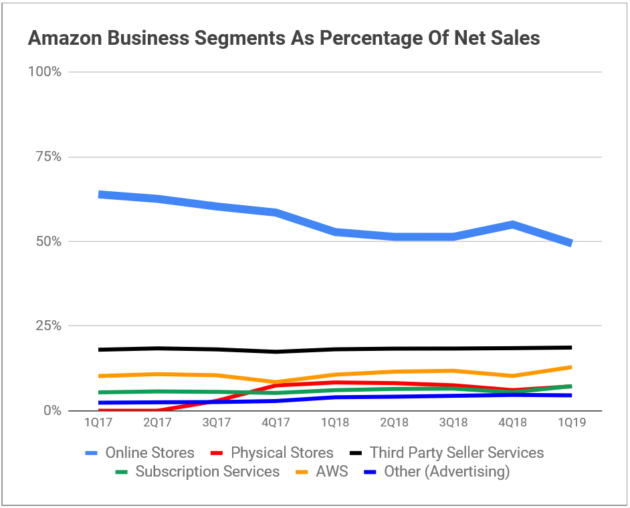

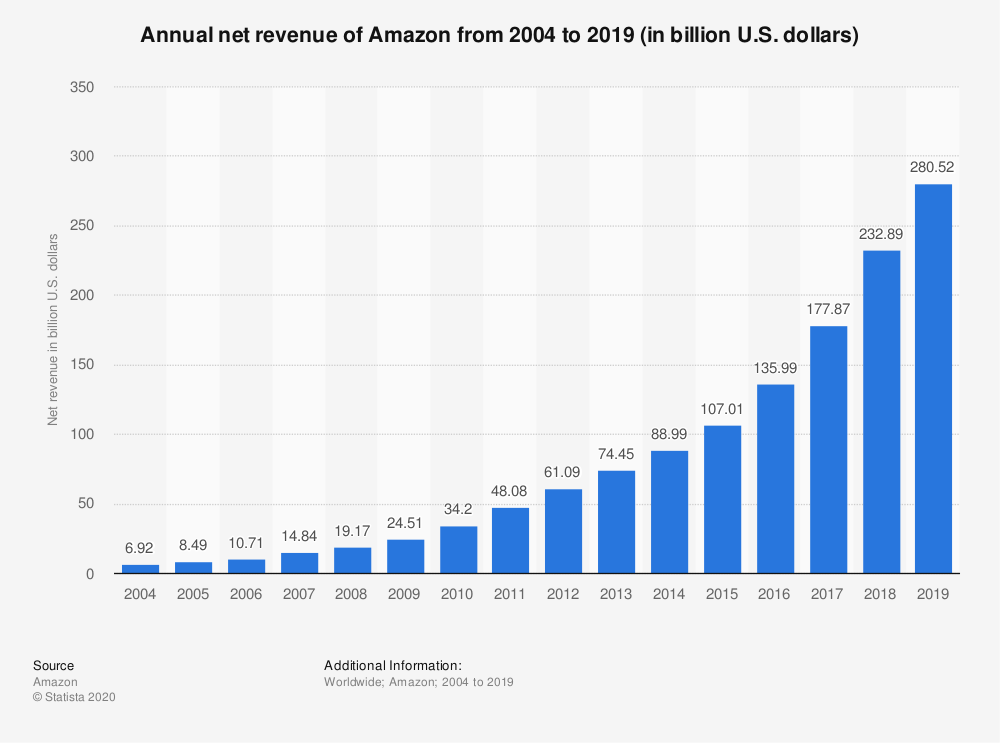

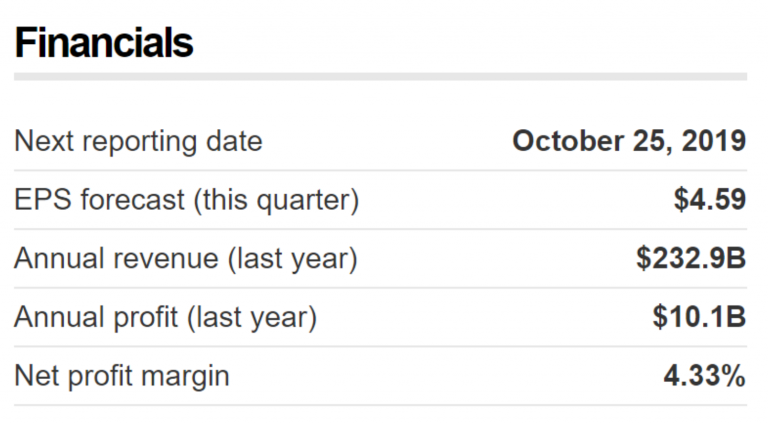

Despite its slowing sales growth in the e-commerce industry, Amazon managed to increase its revenue up to $232.89 billion in 2018 by constantly improving and introducing new products. Amazon still competes within the confines of the existing e-commerce industry and tries to maintain its current customers; at the same time, it makes huge investments into AI and developed uncontested market space of smart devices that made competition in this sector irrelevant. The company’s main AI tool Alexa created a so-called Blue Ocean, a previously unknown market space where demand is created, and cost/differentiation advantages could be achieved simultaneously. Amazon products prove that creating blue oceans builds brands. So powerful is blue strategy, that, in fact, in can create brand equity that lasts for decades.

Traditionally, companies tend to focus on competition in order to expand their market share in the industry and increase profits. Firms, following Porter’s generic strategies presented in his work “Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors” (1980), thrive to achieve a competitive advantage across its chosen market scope opting for either lower cost or differentiation approaches. Thus, all companies within a particular industry seem to compete for a piece of one pie that is composed of the same customers, limited revenue streams and benefits. Such a market space is known as red oceans, where industry boundaries are well defined and accepted, in which the competitive rules are clear, and companies fight against each other for bigger shares of known demand. Certain tendencies in today’s business world such as globalization and technology significantly shrink niche market opportunities and lead to saturation, commoditization and price wars (Kim & Mauborgne, 2005).

From a different perspective, offered by professors W.Chan Kim and Reneé Mauborgne (2005), the market world has another dimension known as blue oceans – a new and unexploited market space untainted by competition where demand is created rather than fought over. As a result, the rules in blue oceans have not been created yet, which makes competition irrelevant and represents an opportunity for new ideas and profitable growth. In order to break free from less profitable red oceans, it is imperative for a company to shift its strategic focus from competition to value innovation which is a cornerstone of the blue ocean strategy. At the same time, firms that wish to succeed in uncharted waters of a new market must deny a conventional idea of tradeoffs between value creation and low price and focus on the pursuit of both differentiation and decreased costs. Regarding long-term benefits, the company that managed to dominate a new market might need to remain its first-mover advantage as long as possible until new competitors enter and make the blue ocean red again. According to the authors, in order to implement the blue ocean strategy, a company has to make a blue ocean shift – particular steps to move from red oceans of bloody competition to the uncontested market: choose the right place to start the initiative; get clear of the current state, discover the ocean of noncustomers; reconstruct market boundaries and, finally, select and test the chosen blue ocean move.

The blue ocean strategy seems to be successful in many industries, especially those involving technology; nevertheless, it is not flawless. it is possible to say that most of the blue ocean new concepts like “non-costumers” or “new market spaces” are just new ways to express old ideas developed in the past by Michael Porter (1980) and others. Another point is that thanks to advanced technology development, the existence period of blue oceans will likely shorten, and new entrants might appear. This speculation might lead back to one of the Porter’s five forces: the threat of new entrants. Amazon’s virtual assistant Alexa has found itself in a similar scenario, which is discussed in this case.

Although nowadays Amazon is the biggest shark in the e-commerce space, it definitely competes in the waters of the red ocean with other strong and well-established companies such as Best Buy, Target, Walmart, Alibaba Group, etc. It has been recently reported that Amazon sales growth slowed in 2018, but the company still positions itself as a profit machine: its total profit for 2018 topped $10 billion for the first time in its history. Here comes a question: how can Amazon maintain its position in a saturated, highly competitive industry? The thing is that only one part of the company competes in the red ocean – its e-commerce industry which works with operations every e-commerce business has: online ordering, checkout processes, fast delivery, returns, etc. These factors are not a source of competitive differentiation. According to Amazon Annual Report (2018), the growing profit comes from other sectors in which Amazon invests heavily: cloud computing, artificial intelligence, consumer electronics and web services in general. Amazon continually tries to create and implement blue ocean strategies in these areas introducing new products such as Kindle, drone delivery and virtual assistant solutions. Such innovations create uncontested space or blue oceans.

One of the most successful products Amazon developed is called Echo, a smart speaker that connects to the voice controlled intelligent personal assistant service Alexa (nowadays the words “Echo” and “Alexa” are used interchangeably). There are many features the device includes: voice interaction, music playback, making to-do lists, setting alarms, streaming podcasts, playing audiobooks, providing weather, traffic and other real time information.

Echo is being constantly improved and now is able to work as a part of IoT and act as a home information hub. Alexa has become a sleeper hit that could set a future industry standard in case more competitors come, but for now Amazon can enjoy its first-mover advantage and even move forward.

The company came a long way in an attempt to develop the world’s most famous virtual assistant. Trying to understand and predict future opportunities, the first step the company took was the detection of new trends in the market: it is assumed that Siri was the first voice assistant that reached a wide audience but was not able to create a blue ocean since it had a limited set of actions and was available only on IOS devices (Mutchler, 2017). At the same time, it can be argued that since the first company to introduce a virtual assistant was Apple, Amazon probably cannot be considered the first mover who created a blue ocean; conversely, Alexa entered a “purple” ocean where competition was not null and a new market was being formed.

The creation of Siri, in any case, served as a wake-up call for Amazon managers that pushed them for a change. As a result, the company started the reconstruction of its market boundaries by assuming several paths as strategies mentioned in the work of W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne (2005). Amazon looked across alternative industries, the chain of buyers and functional/emotional appeal to buyers at the same time. AWS (Amazon Web Services) has proved to be a more profitable area for the company; Alexa, in particular, could generate between $18 billion and $19 billion in total sales by 2021, or around 5% of Amazon’s total revenue, according to a new report from RBC Capital Markets analysis (2018).

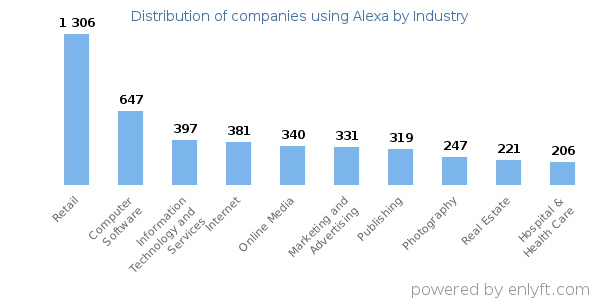

It is important to note that Alexa device does not converge on a single buyer group: it focuses on both B2B and B2C commerce. On the one hand, a personal use of Alexa includes playing music and games, asking questions and controlling smart home devices, such as light, fans and thermostats in the buyer’s house. But Amazon did not stop here: built in the cloud, Alexa always gathers more information and becomes smarter, so it can be used in the corporate world too. The virtual assistant can inform you about purchase history, office supplies refills and even generate corresponding documents. The device can be connected to everything starting from lawn mowers to laptops; currently more than 18.000 companies use Alexa with almost 2000 of them being in the retail and computer software industries mainly in the US. Finally, emotional appeal is a point of strength of Alexa: according to Microsoft analysis, Alexa’s broader success resides in its ability to alleviate stress of an overbooked life. With the simple action of asking Alexa relieves the negative emotions or uncertainty and the fear of forgetting; it seems like a companion that is always ready to engage (Austin, 2017). Thus, the product has a dual functional and emotional appeal.

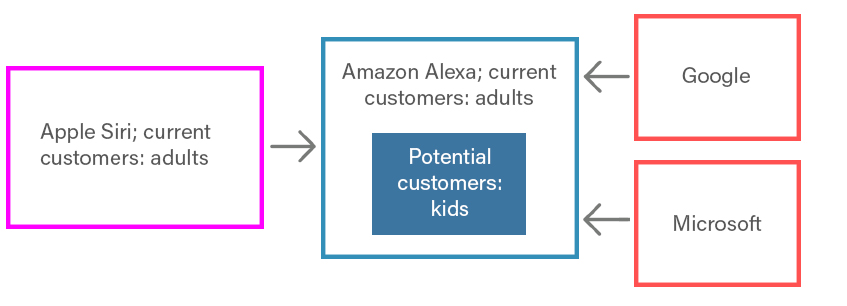

A major component of value innovation is to maximize demand by reaching beyond existing customers, which means seeking ways to attract noncustomers. Current Amazon Alexa demographics are mostly male millennials, specifically, 19-30 years old (Koksal, 2018). The type of Amazon’s noncustomers can be called as “unexplored noncustomers”: industry has always ignored them as they are assumed to be loyal to other products or the product for them simply does not exist yet. These noncustomers have already been identified by the company – kids. Amazon has been making a push for child-focused Alexa devices and skills. According to the information provided by Forbes (2018), it launched its first Echo Dot Kids Edition and is hoping to expand its userbase to children with safe and child-compatible products. This way the company is trying to create a new demand that has not been explored by other companies yet. As Alexa is already navigating blue waters, it seems that Amazon has a long-term vision trying to expand the boundaries of its existing blue ocean by exploring noncustomers segment. To some extent, it is currently developing a new blue ocean inside the existing one, which can be represented in the chart below:

In terms of financing, it is clear that Amazon does not need to overcome any resource hurdles since the company is already a top player in the market, which makes it also impossible for other companies to beat Amazon. In 2017 Amazon invested $23 billion on R&D development particularly in AWS (Fuscaldo, 2019). Such heavy costs must be recouped as fast as possible, so the need to build sales volume quickly is more important than in the past: setting the right strategic price is critical to attracting new customers in large numbers. Also, a new offering that combines exceptional utility with an attractive pricing is hard for competitors to imitate. Amazon made a similar play here: the firms original Echo device was priced at $199, but already in 2016, the firm released a revamped lower end offering, the Echo Dot, only for $50. That device’s popularity propelled the Echo installed base to 9 million US household – a figure that continues to grow until now (Shields, 2017).

Following the blue ocean strategy, Amazon also recognized the importance of partnerships with the objective to leverage its expertise, economies of scale and create new markets. In 2016 the company partnered with SAP in order to be able to perform business tasks and explore the possibility of future B2B sales. Another example is Amazon’s partnership with Cisco to build software tools to integrate Cisco with the Alexa: the virtual assistant connects with conferencing equipment providers, such as Cisco Telepresence and Zoom Rooms to simplify the conference experience (Somasundaram, 2018). But Amazon has its long-term objectives too: the company uses its partnerships for future innovations. Navigating blue oceans can dramatically increase the chances of success, but Amazon is aware that last week’s blue ocean is next week’s red ocean as innovation will be imitated. The key to long-term sustainability and renewal is to dominate the market space for as long as possible, while continually monitoring the changing scenario. When an innovator’s value curve begins to converge with that of the competition, it is time to create more blue oceans. Indeed, possible competition is already looming: Google is reportedly working in a smaller, less expensive version of its already existing Google Home smart speaker; Apple and Microsoft are also planning to get into the space, although their offerings are likely to be costly, so Amazon can still keep its edge in the uncharted waters. But the company needs to keep moving and keep innovating. Alexa smart assistant is just one device that can spark future development: the company created Echo buds, Echo frames, loops, Flex plugs and Amazon Sidewalk devices to connect to Alexa in order to provide a trusted and compatible service as well as to bring the device closer to the user. Over time, the company also created other versions of its Echo devices, such as Amazon Tap, Echo Dot, Echo Spot, Echo Auto, to name a few. One of the latest inventions was Echo Look that represents a camera with Alexa built in. The device can take pictures or videos and provide artificial intelligence outfit recommendations and does not have any competitors so far.

One of the features of a blue ocean strategy is the absence of market rules, tendencies and even laws. Almost all digital devices mentioned above epitomize some sort of tension between efficiency and privacy (Lynskey, 2019). According to digital rights specialists, virtual assistants can be co-opted in undesirable ways by large multinationals and state surveillance systems or compromised by malicious hackers. Technology companies’ business models usually depend on the knowledge about their customers in order to micro target advertising (Eadicicco, 2019). A possible solution to the problem might appear if a particular firm takes a lead and establishes a future market standard regarding human monitoring. Thus, new entrants would thrive to achieve safe and user-controlled voice assistants, which, by this time, will have become an industry requirement.

In general, the value innovation stands in stark contrast with the conventional practice of technology innovation. Despite existing criticism, there is a great potential for economies of scale, learning and growing returns in the world of new ideas and knowledge. Blue ocean strategy delivers a path-breaking message that can inspire innovation in companies across industries and around the globe. Inherent in blue ocean strategy are significant barriers to imitation.

While some argue that creating new demand and turn to noncustomers can be fruitful, other scholars believe that large corporations can have a two-pronged approach: increasing current customers’ lifetime value and, at the same time, trying to attract noncustomers and, as a consequence, create new demand. In case of Amazon, the latter approach worked. Most of its profit comes from the red ocean operations in e-commerce, an industry that appeared before Amazon was founded and, even so, Amazon was able to enter this red ocean, grow and turn into a market leader. While sailing in the red ocean in e-commerce, the company explored the blue ocean in AWS. Such a double approach might work in large corporations, whereas SME will probably have to choose whether they will keep a bloody fight within the existing rules, or they are ready to innovate and find growth opportunities in the uncontested market space.

Whatever the industry is, there is always an opportunity to discover a blue ocean through the search of new customers and new markets. However, leaning from Amazon Alexa case, a second possible lesson would be completely different: being profitable by being simply more competent than your rivals in red oceans. There is money in traditional markets too.

--------------------

References:

Amazon Annual Report (2018)Retrieved from: https://ir.aboutamazon.com/static-files/0f9e36b1-7e1e-4b52-be17-145dc9d8b5ec

Anders, G. (2017). “Alexa, Understand Me”. Retrieved from: https://www.technologyreview.com/s/608571/alexa-understand-me/

Austin, D. (2017). This is how Amazon’s Alexa hooks you. Retrieved from: https://www.invisionapp.com/inside-design/amazon-alexa-hook/

Clement, J. (2019). Amazon: annual revenue 2004-2018. Retrieved from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/266282/annual-net-revenue-of-amazoncom/

Clement, J. (2019). Global net revenue of Amazon 2014-2018, by product group. Retrieved from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/672747/amazons-consolidated-net-revenue-by-segment/nt/ Companies using Alexa (n.d.) Retrieved from: https://enlyft.com/tech/products/alexa

Competing against Amazon? You Need a Blue Ocean Strategy! (n.d.). Retrieved from: https://supplychaingamechanger.com/e-commerce-part-7-competing-with-amazon-develop-your-blue-ocean-strategy/

Eadicicco, L. (2019). Amazon workers reportedly listen to what you tell Alexa – here’s how Apple and Google handle what you say to their voice assistants. Retrieved from: https://www.businessinsider.com/how-amazon-apple-google-handle-alexa-siri-voice-data-2019-4

Fiegerman, S. (2019). Amazon has its first $200 billion sales year, but growth is slowing. Retrieved from: https://edition.cnn.com/2019/01/31/tech/amazon-earnings-q4-2018/index.html

Five Year Financial Summary (n.d.). (2019). Retrieved from: https://money.cnn.com/quote/financials/financials.html?symb=AMZN

Frankenfield, J. (2019). How Amazon Makes Money. Retrieved from: https://www.investopedia.com/how-amazon-makes-money-4587523

Fuscaldo, D. (2019). Amazon’s $23B R&D Budget Sets a Record: Recode. Retrieved from: https://www.investopedia.com/news/amazons-23b-rd-budget-sets-record-recode/

Hello, this is B1 Assistant speaking. What is my command? (n.d.), (2017). Retrieved from: https://www.blueoceansys.com.sg/blog/hello-b1-assistant-speaking/ Information for SAP partners (n.d.) Retrieved from: https://aws.amazon.com/pt/sap/for-partners/ Investor Relations. (2019). Retrieved from: https://ir.aboutamazon.com/news-releases/news-release-details/amazoncom-announces-first-quarter-sales-17-597-billion?tag=theverge02-20

Kim E. (2016). Here’s another sign that Amazon is betting on Alexa, its smart personal assistant. Retrieved from: https://www.businessinsider.com/amazon-to-have-alexa-session-track-at-annual-aws-conference-2016-7

Kim W.C., Mauborgne R. (2005). Blue Ocean Strategy: How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make the Competition Irrelevant. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Koksal I. (2018). Who’s the Amazon Alexa Target Market, Anyway? Retrieved from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/ilkerkoksal/2018/10/10/whos-the-amazon-alexa-target-market-anyway/#5f9863582eb5

Lynskey, D. (2019). “Alexa, are you invading my privacy?” – the dark side of our voice assistants. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/oct/09/alexa-are-you-invading-my-privacy-the-dark-side-of-our-voice-assistants

Mejia, Z. (2018). Jeff Bezos finally got Amazon into the tip tier of the Fortune 500. Retrieved from: https://www.cnbc.com/2018/05/23/jeff-bezos-finally-got-amazon-into-the-top-tier-of-the-fortune-500.html

Moorhead, P. (2019). Five Top Themes from Amazon’s Alexa and Echo Event You Need To Know. Retrieved from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/patrickmoorhead/2019/09/25/five-top-themes-from-amazons-alexa-and-echo-event-you-need-to-know/#7a6bb6a528c4

Muchler, A. (2017). Voice Assistant Timeline: A Short History of the Voice Revolution. Retrieved from: https://voicebot.ai/2017/07/14/timeline-voice-assistants-short-history-voice-revolution/

Porter, M.E. (1980). Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors. New York, NY: Free Press.

Shields, N. (2017). Google targets Amazon’s smart speaker price advantage. Retrieved from: https://www.businessinsider.com/google-amazon-echo-dot-price-advantage-2017-8

Somasundaram, M. (2018). Setting up Alexa for Business with Cisco Telepresence video conferencing. Retrieved from: https://aws.amazon.com/pt/blogs/business-productivity/setting-up-alexa-for-business-with-cisco-telepresence-video-conferencing/

Ungarino, R. (2018). Amazon’s Alexa could be a $19 billion business by 2021, RBC says (AMZN). Retrieved from: https://markets.businessinsider.com/news/stocks/amazon-stock-price-alexa-19-billion-business-rbc-says-2018-12-1027829391

Watkins, M.D., Clayton, M., Christensen, M. Kenneth, L. K., Porter, M.E. (2013). Leadership Library: The Executive Collection. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from: https://books.google.com.br/books?id=jvKECgAAQBAJ&pg=RA1-PA8&lpg=RA1-PA8&dq=commoditization+and+price+wars+harvard+business+review&source=bl&ots=GUJli2yqAi&sig=ACfU3U0VXL_zbKWX-J1fra8zV58r_fURsA&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiRjLO_7a3lAhVPLLkGHaozBtMQ6AEwEHoECAkQAQ#v=onepage&q&f=false